Real life scenario

You receive a flyer at home with a special discount on Jack Daniels at your favorite store. 50% off today. You arrive at the store. You look at the shelf price of your upcoming alcoholic beverage. It displays the 50% off sticker. Cool!

Hmm…Wait. You’re looking closer and the actual price is not 50% but the regular price you normally pay. You’re upset and you contact the store manager to find out what’s going on.

Does this scenario sounds familiar? Probably not. Why? Because in the world of retail there are rules and regulations about promotions, discounts and advertising.

You can’t just organize fake discounts and claim it is is a cool discount to attract users.

Now back to the App Store.

Apple and Google give developers the ability to change the price of the apps they built quite easily. Price increase or price decrease, the developer has the control (with the lone restriction that Google blocks developers from setting a price on their app once it’s been made free. God knows why…)

Organizing a price promotion is a great marketing tool to find out the right pricing for your app, but also to accelerate adoption. Apple organizes a Free App of the Week (example below) every week and there are many services that help surface those promotions too (Disclosure: Appsfire is one of them).

But this is also something many developers or services are manipulating to fool users and make them believe there is an opportunity here. And here, unlike in the “real retail world”, there is no chance to find out what is a “real promotion” or a fake one. Why? Because the App Store only displays the price at the moment of your visit and there is no reference to price evolution.

If a developer claims “200%” off at $0.99 how can you really find out if the price was $2.99 just before? Maybe it was only $0.99?

There’s more to it. As a developer you can change the price as many times as you want. And in theory you can organize price discounts as many times as you want. In that context, how can you know if the discount applies to a price that truly represents the standard price?

The reality is that the App Store is full of fake deals: deals that are either deceptive or misrepresentative.

Here are the varieties of fake deals:

- Fake price drops: The app claims it’s on sale in its app description, when in reality the price has never changed.

- Inaccurate price discount: The app claims a X% discount, when in reality the magnitude of the discount is smaller. For example, the app that has recently gone free claims that it’s down from $5.99, when in reality the all-time high price of the app was $3.99.

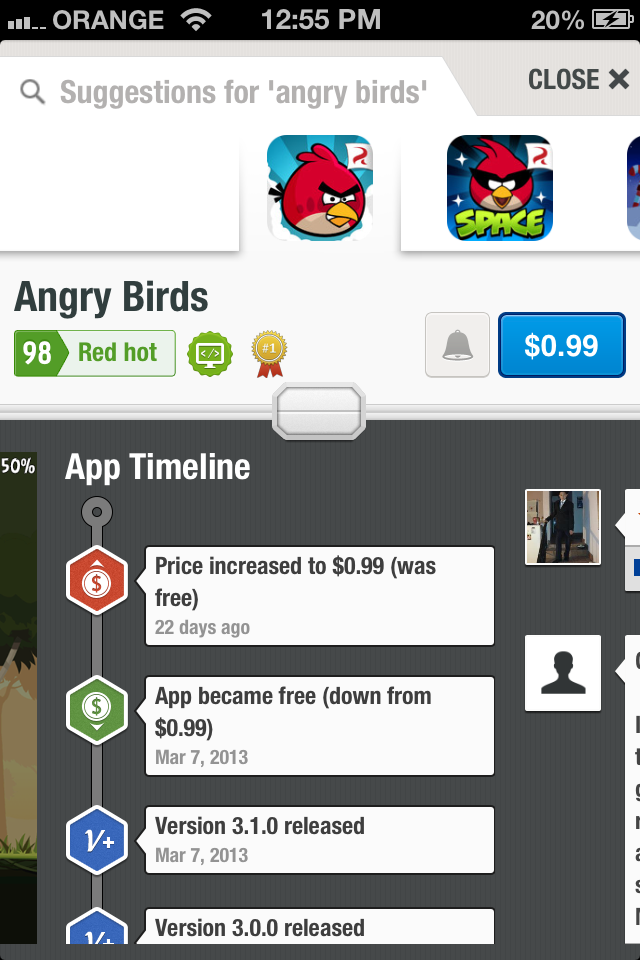

- Artificial discount (screenshot below): An app that just launched or is normally worth X will artificially raise the price up to Y for a day or two and then will drop the price back to X, claiming it as a “discount”

- YoYo Apps or High-Frequency Price Droppers: Apps in “promotion” every few days.

- Paid to Freemium: A paid app is indeed becomes free, but the price is now applied in in-app purchase (nothing wrong with that…unless the developer claims “FREE TODAY”)

- Fake “free today”: The app claims it’s “free” today. In reality it’s free all the time or the vast majority of the time.

- Fake In-App bonus: The app claims “$X worth of In-App Purchase” and offers no way to redeem this bonus or offers no in-App bonus. Or it offers an In-App bonus that does not have the value it claimed.

The good news is that the App Store is full of legitimate promotions like the recent price drop organized by Apple and Rovio on Angry Birds.

So what do we do with this? It’s all about trust

Users have to consider carefully what they download. They can use third-party services (like Appannie or others..) to find out the price history of an app. Appsfire offers such a feature (more on that coming soon).

Unfortunately many app guides or review sites list all those “discounts” and scams as if they were equal, and many “app marketing services” and ad networks do not hesitate to also use those techniques to create the illusion of a “deal” and create a stronger marketing leverage.

Apple and Google could be more careful by limiting the number of times a developer can change their pricing or by limiting the ability to update the app description (as Apple recently did with the app title). Maybe a firm, operationally-enforceable rule on this point would be welcome.

It is critical users can trust developers. Quality discovery is based on trust. If you rupture that trust, discovery is broken.